Research

I - Past Research

1) Wavelets (1992–2000): Hardware Mitigation, Image Restoration & Non-Gaussian Noise

The first decade of my work was defined by the struggle to extract signals from instruments operating in the harsh, unpredictable environments of space.

- The Wavelet Deconvolution (HST): I pioneered the application of multiscale wavelet-based methods to recover high-resolution information from aberrated data sets. This notably included early Hubble Space Telescope (HST) images affected by the primary mirror’s spherical aberration prior to corrective servicing. This work established a foundational framework for modern astronomical image restoration, demonstrating that sparse representations could effectively handle complex point spread functions (PSF) in space-based imaging.

- ISO and the Cosmic Ray Challenge: In the Infrared Space Observatory (ISO) mission, data were heavily corrupted by non-Gaussian cosmic ray hits and transient effects. I pioneered wavelet-based solutions for calibration and galaxy detection methods (Starck et al., 1999) specifically designed to distinguish real high-z sources from instrumental artifacts. This enabled the first deep infrared surveys (Elbaz et al., 1999), fundamentally changing our view of dust-obscured galaxy evolution.

- XMM & Fermi: Mastering Poissonian Signatures: High-energy instruments like XMM-Newton and Fermi operate in the Poisson noise regime, where standard Gaussian assumptions fail. I proposed a robust wavelet solution for deriving source catalogs (Starck & Pierre, 1998; Abdo et al., 2010) that accounted for the specific statistical properties of X-ray and Gamma-ray photon counting. This method is still currently used in the XMM-LSS pipeline more than 20 years later, not yet outperformed by deep learning techniques.

-

-

2) Pioneering Multiscale Analysis and the Sparsity Revolution (1992–2010)

As surveys grew larger, the problem shifted from individual pixels to the geometry of the mission, dealing with missing data, masks, and systematic offsets. We have developed several concepts, Curvelets transform (Starck et al 2002), Sparse Inpainting (Elad et al, 2005), Morphological component Analysis (CMCA) (Starck et al, 2005) and Generalized Morphological component Analysis (GMCA) (Bobin et al 2007), as well as their extension to 3D (Starck et al, 2005; Woiselle et al, 2010), spherical (Starck et al, 2006) and 3D spherical data set (Lanusse, et al, 2012). These concepts have then be applied on different space projects:

- The "Inpainting" Paradigm: Space missions are plagued by "missing data" due to bright foreground masks or detector gaps. We show that sparse inpainting can mitigate the systematics relative to missing data in scientific studies such as Planck Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) weak lensing (Perotto et al, 2010) or Hubble Space Telescope (HST) weak lensing mapping (Massey et al., 2007).

- Component Separation and the Discovery of Filaments (Herschel):: The star formation filaments discovered by the Herschel space telescope (André et al., 2010) were originally buried under complex galactic foregrounds. My development of Morphological Component Analysis (MCA) (Starck et al., 2004) allowed us to "de-mix" the signal, separating instrumental and galactic contamination from the physical filaments based on their unique morphological signatures.

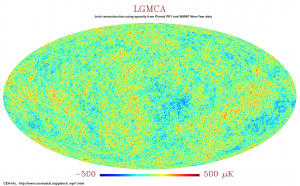

- Blind Source Separation and Planck data set: foregrounds is a very challenging systematics for many cosmological studies. Our extension of MCA to multichannel data set provides a complete new framework for blind source separation, and a new approach to mitigate systematics. We introduced this concept to the CMB community (Bobin et al, 2013). This enabled the derivation of the very clean joint WMAP/Planck CMB map (Bobin et al., 2014), which remains the unique standard for sensitive kinetic Sunyaev-Zeldovich studies. This framework was also extended so as to deal with non-negative mixtures of non-negative sources (non-negative matrix factorization, NMF, (Rapin, Bobin, Larue, Starck, IEEE Trans. on Signal Processing, 2013) and (Rapin, Bobin, Larue, Starck, SIAM Journal on Imaging Sciences, 2014; Rapin et al, Signal Processing, 2016). It was also shown that sparse BSS is extremely efficient to recover the epoch of reionization (EoR) signal (Chapman et al, MNRAS, 2013), which is an extremely low SNR signal informing us about the Universe's dark ages end with the formation of the first galaxies.

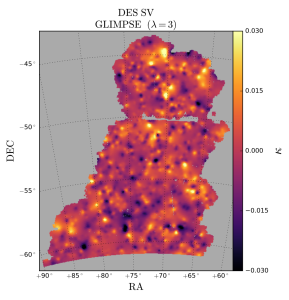

- From Signal Processing to Cosmic Cartography: The First Dark Matter Maps: We developed GLIMPSE, a sparse reconstruction code for weak lensing convergence maps in 2D and 3D. This work established the "Gold Standard" for cosmic shear analysis and led to my appointment as the lead for the Euclid Science Ground Segment (SGS) organization unit for Level-3 products.

-

-

- Radio-Interferometry Image Reconstruction: a very cool result !Compressed Sensing and Sparse Recovery: A new paradigm to transfer data from satellite to earth (Bobin et al, 2008) has been proposed.

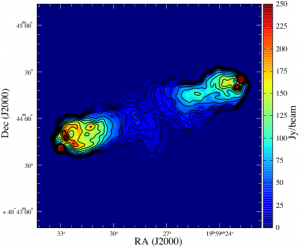

Radio-Interferometry Image Reconstruction: a very cool result ! In Radio astronomy, Sparse recovery allows us to reconstruct an image with a resolution increased by a factor two (Garsden, Girard, Starck, Corbel et al, A&A, 2015). This has been confirmed by comparing two images of the Cygnus A radio source, the first from the LOFAR instrument and reconstructed using sparsity, and the second one from Very Large Array at a higher frequency (and therefore with a better resolution). The contour the VLA image matches perfectly the high resolution features that can be seen in the LOFAR color map image. More details here.

Radio-Interferometry Image Reconstruction: a very cool result ! In Radio astronomy, Sparse recovery allows us to reconstruct an image with a resolution increased by a factor two (Garsden, Girard, Starck, Corbel et al, A&A, 2015). This has been confirmed by comparing two images of the Cygnus A radio source, the first from the LOFAR instrument and reconstructed using sparsity, and the second one from Very Large Array at a higher frequency (and therefore with a better resolution). The contour the VLA image matches perfectly the high resolution features that can be seen in the LOFAR color map image. More details here.

- Radio-Interferometry Image Reconstruction: a very cool result !Compressed Sensing and Sparse Recovery: A new paradigm to transfer data from satellite to earth (Bobin et al, 2008) has been proposed.

3) Cosmology using Sparsity (2010–2020)

- Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB): The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is a relic radiation, which was emitted 370,000 years after the Big Bang at the epoch of recombination. This is when our Universe became neutral and transparent. The CMB radiation has travelled the Universe since decoupling and its precise measurement is critical to observational cosmology.

Using both WMAP and Planck PR1 data, we have reconstructed an extremely clean CMB map. A more detailed description can be found here. The same method has been used on Planck and PR2 data (Bobin et al, 2016). We have shown that large scale analysis does not require masking anymore when using our estimated CMB map (Rassat et al, 2014), and that CMB large scales are compatible with the standard l-CDM cosmological model (Rassat et al, 2014). More details can be found here. Finally, we have estimated the primordial power spectrum using our PRISM method on both WMAP9 (Paykari et al., A&A, 2014) and Planck data (Lanusse et al., A&A, 2014) and we find no significant departure from the Planck PR1 best fit. Similar results were obtained with Planck PR2 (Bobin et al, 2016).

- Spatial/Color Distribution of Galaxies:

- New data require new representations. We have investigated benefits of performing a full 3D Fourier-Bessel analysis of spectroscopic galaxy surveys, such as the Euclid spectroscopic survey, compared to more traditional tomographic analysis. We have shown that the 3D analysis optimally extracts the information and is more robust to uncertainties on the coupling between the galaxies and the dark matter (Lanusse, Rassat and Starck, A&A, 2015).

- Late type/Early type galaxy separation: We have also shown how sparsity can help to separate automatically early type galaxies from late type galaxies, using multichannel data set (Joseph et al, A&A, 2016). Such a method could be extremely useful for Strong Lensing. See here for more details.

- Weak Lensing:

- 2D mass mapping:

Using both shear and flexion, we have shown how very high resolution convergence maps can be reconstructed (Lanusse et al, 2016). For example, Glimpse was used to reconstruct the mass distribution in the Abell 520 merging galaxy cluster system using Hubble Space Telescope observations (Peel et al, 2018). Glimpse has also been used to map the matter density field of the Dark Energy Survey (DES) Science Verification (SV) data (Jeffrey et al, 2018). More details are available here. We have also developed a new approach, based on machine learning, which looks very promising. Using this method, we made the first reconstruction of dark matter maps from weak lensing observational data using deep learning (Jeffrey et al, 2020). More details are available here.

-

- The 3D tomographic mass mapping:

Underlying the link between weak lensing and the compressed sensing theory, we have proposed a completely new approach to reconstruct the dark matter distribution in three dimensions using photometric redshift information (Leonard, Dupe et Starck, 2012; Leonard, Lanusse et Starck, 2014), and we have shown we can estimate with a very good accuracy level the mass and the redshift of dark matter haloes, which is crucial for unveiling the nature of the Dark Universe (Leonard et al, 2015). More details are available here.

Underlying the link between weak lensing and the compressed sensing theory, we have proposed a completely new approach to reconstruct the dark matter distribution in three dimensions using photometric redshift information (Leonard, Dupe et Starck, 2012; Leonard, Lanusse et Starck, 2014), and we have shown we can estimate with a very good accuracy level the mass and the redshift of dark matter haloes, which is crucial for unveiling the nature of the Dark Universe (Leonard et al, 2015). More details are available here. -

-

- Point Spread Function Modeling: For weak lensing shear measurements to be useful for cosmological studies, it is also necessary to model properly the point spread function (PSF) of the instrument. In the case of the Euclid project, this PSF is subsampled, and we have proposed a method (Ngolè, Starck et al, A&A, 2014; Ngolè, Starck et al, 2016) to achieve surperresolution, which will increase the cosmological constraining power of Euclid significantly. See here for more details. We have also investigated optimal transport technique to take into account the wavelength dependancy of the PSF (Ngolè et Starck, A&A, 2017; Schmitz et, 2018, Schmitz et al, 2020). Graph theory has be found to very useful to derive a regularized field of PSF (Scmitz et al, 2020). This approach has led to the developed of a new PSF field recovery method (Tobias et al, 2021), MCCD, which has been used to analyse the CFIS survery

II - the Deep Learning Era (2015-Present)

The current phase of my research marks a transition from treating AI as a "black box" to integrating it into the fabric of physical laws. While deep learning offers unprecedented flexibility, my work focuses on ensuring these models maintain the mathematical rigour and reliability required for "discovery-class" science.

- Deep Learning versus Wavelets: We explored the synergy between classical multiscale analysis and artificial intelligence by introducing "Learnlets," a wavelet-like filter bank learned within a deep learning framework (Ramzi et al, 2022). It demonstrates that by enforcing structural constraints derived from wavelet theory, neural networks can achieve state-of-the-art denoising performance while maintaining the interpretability and exact reconstruction properties of traditional transforms.

- Physics Informed Deep Deconvolution : We introduced a physics-enhanced deep learning method for weak lensing mass mapping and image deconvolution by embedding the Point Spread Function (PSF) directly into a neural network architecture. It demonstrates that this approach achieves superior restoration of astronomical images while maintaining strict consistency with the known physical properties of the telescope (Akhaury et al, 2022)..

- Probabilistic Mapping with Neural Scores: We have pioneered Neural Score Estimation for mass mapping (Remy et al. 2023). By using score-based generative models, we can now sample from the posterior distribution of the dark matter field. This provides not just a single map, but a full probabilistic ensemble, enabling rigorous uncertainty quantification, a prerequisite for "Discovery-Class" science in the Euclid era.

- The Hallucination Problem: We introduced the Conformal Hallucination Estimation Metric (CHEM) to quantify and analyze hallucination artifacts in image reconstruction models, using wavelet/shearlet features and conformalized quantile regression to assess hallucinations in a distribution-free way. It also investigates why U-shaped networks (e.g., U-Net, SwinUNet) are prone to hallucinations and validates the approach on the CANDELS astronomical dataset, offering insights into hallucination behavior in deep learning image processing.

- Beyond Point Estimates: Sampling-Free Uncertainty: A major bottleneck in AI-driven cosmology is the "black-box" nature of neural reconstructions. We developed sampling-free uncertainty quantification using Moment Networks and Conformal Quantile Regression (CQR). This provides frequentist-valid confidence intervals for every pixel in a mass map without the prohibitive computational cost of Monte Carlo simulations or Bayesian sampling (Leterme et al, 2025).

III - Weak Lensing (2020-Present)

- WaveDiff – Beyond Empirical PSF: Traditional PSF modeling for Euclid relies on empirical interpolation, which fails to capture high-order wavefront perturbations. We have developed WaveDiff (Liaudat et al., 2023), moving the problem into the physical domain of Phase Retrieval. By utilizing automatic differentiation, we can perform phase retrieval directly on the telescope’s wavefront. This allows us to recover for the first time the Wavefront Error (WFE) as a non-parametric field, using only in-focus stars, accounting for the actual mechanical state of the telescope.

- Information Extraction via the Wavelet l1-norm: Standard cosmological analysis focuses almost exclusively on the 2-point power spectrum, effectively discarding the rich non-Gaussian information contained in the cosmic web. We proposed the starlet l1-norm (Ajani et al. 2021; Sreekanth et al. 2024), a multi-scale statistic proven to be more sensitive to non-linear structures than traditional methods. By linking these higher-order moments to Simulation-Based Inference (SBI), we provide a new channel for testing the ΛCDM model with significantly tighter constraints on Ωm and σ₈ (Tersenov al, 2026).